For nearly 10 years, U.S. Marine Veteran Kenny Berning lived with lingering heartburn and shortness of breath. He scheduled multiple appointments during that decade with providers at his local Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital, searching for a diagnosis that could explain what was wrong.

“I just didn’t feel good, and I was always out of breath. I couldn’t walk 100 feet without grabbing a handrail or chair,” says the 67-year-old self-employed truck driver who drives over 360 miles a day. “The cardiologists at the VA ran stress tests, echocardiograms, MRIs and pretty much everything else. When they gave me a diagnosis, they told me I needed to see a specialist.”

Kenny had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), an inherited condition that thickens the heart muscle and makes it harder for the heart to pump. A cardiologist at a nearby hospital told him he needed expert care and urgent surgery and suggested he seek care at an out-of-town nationally known hospital. But he quickly learned that expert care of HCM is available in his hometown. In August 2023, Kenny was referred to the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Center at The Christ Hospital, Greater Cincinnati’s first HCM Center of Excellence.

One month later, Kenny underwent a single surgery that included four separate procedures. It was a high-risk operation that saved his life.

A complicated diagnosis

Once he arrived at The Christ Hospital, Kenny saw Wojciech Mazur, MD, a cardiologist and co-director of the HCM Clinic, and J. Michael Smith, MD, a thoracic and cardiac surgeon. They evaluated Kenny’s condition, reviewed his medical record and, together with a multidisciplinary team, determined he needed surgery as soon as possible.

“He was going downhill. Many other hospitals considered him too high risk to attempt surgery, but he was dying,” Dr. Mazur says. “Death may soon have been his outcome had we not proceeded with surgery.”

Dr. Mazur used a detailed 3D model to help Kenny understand the state of his heart. Using that model, he demonstrated that HCM wasn’t Kenny’s only problem. He also had several blood vessel blockages, an aortic valve that wouldn’t open and a mitral valve that leaked. These conditions further reduced his blood flow and caused his shortness of breath. Fixing these issues required an intricate surgery that few surgeons could complete successfully.

At first, Kenny says he was unsure about undergoing surgery. Instead, he was more interested in spending his remaining time with his family and riding his Harley-Davidson motorcycle. Even if he felt bad most of the time, he didn’t want to risk anything going poorly with surgery and missing an extra six months of life. Eventually, he changed his mind.

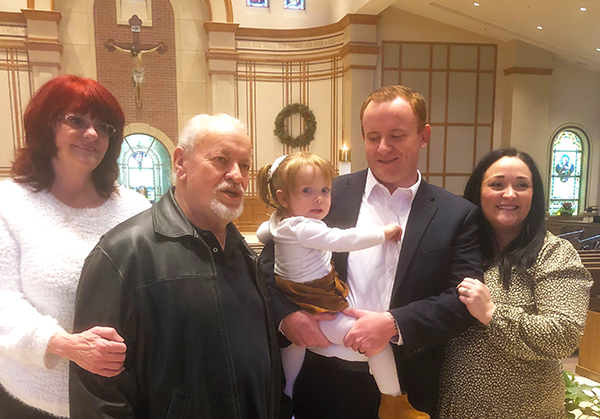

“I was getting weaker and weaker before the surgery,” he says. “Then, at one point, my son put my new grandbaby Harper in my arms. At that point, I knew I needed to go through with the operation.”

A complex surgery

To repair his heart and restore his quality of life, Kenny faced the potential of nearly eight hours of surgery and four separate procedures. Like all patients with HCM, he needed a septal myectomy (an open-heart procedure that removes some of the thickened heart muscle to improve blood flow). His operation also included a triple coronary bypass (an operation that reroutes blood around three blocked arteries) to clear his blocked arteries and two valve replacements.

The procedure was exceedingly difficult. Completing all four procedures at once meant juggling multiple complications, like possible blood vessel damage, rupture, or excessive blood loss. It also meant stopping Kenny’s heart for an unusually long time. Consequently, the surgery presented a higher-than-average risk of mortality compared to procedures involving fewer repairs and complications.

Dr. Smith, the region’s leading HCM surgeon, embraced the challenge and completed Kenny’s surgery on Sept. 5, 2023.

“This was a really big operation that most surgeons would not elect to take on,” he says. “Even with all of the different complications, it made sense to do the surgery because someone like Kenny would undoubtedly die without it. His odds of returning to a healthy life were much higher if he had the operation.”

Thanks to a collaborative effort with anesthesiologists, perfusionists (medical professionals who operate machines that support heart and lung function during operations) and surgical assistants, Dr. Smith successfully performed the operation. And he completed it in a fraction of the expected time. The surgery lasted slightly more than three hours, and he limited the time Kenny’s heart was stopped to 2.5 hours.

A rocky but positive recovery

The surgery went well, but Kenny’s recovery was slow. Even as his heart function strengthened, he developed complications.

The surgery went well, but Kenny’s recovery was slow. Even as his heart function strengthened, he developed complications.

Within a few days, his kidneys started to fail, a common complication with this surgery. His levels of creatinine (the waste product usually filtered by the kidneys) spiked. As a result, he received dialysis almost daily for several weeks. Providers initially thought he would need the treatment permanently. But his kidney function rebounded by the time he left the hospital.

In addition, Kenny experienced a complication rarely seen with open-heart surgery patients. He developed an antibody that caused his body to resist heparin (a blood-thinning medication), increasing his risk for blood clots. To eliminate this problem, providers switched his medication.

Despite these stumbling blocks, Kenny thrived with physical therapy and cardiac rehabilitation. After resisting rehabilitation efforts at first, he soon welcomed the opportunity to work daily with The Christ Hospital’s therapists.

“I was very ornery about physical therapy at first, but I soon really got into it,” he says. “The therapists were supportive, and I realized that I didn’t want anyone else taking care of me. So, I pushed myself to walk farther and to do more.”

One year after surgery, Kenny is back at work on the road. He’s built and painted two decks,and traveled to South Dakota for the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally.

“Life is better than normal now. I’m like a solid used car. I’ve got a remanufactured heart. And I figure whatever God is going to give me, I can handle it,” he says. “On a scale of 1 to 10, The Christ Hospital and the team that takes care of patients like me are an 11.”

The Christ Hospital impact

Dr. Mazur says The Christ Hospital is uniquely positioned to deliver this high level of care. The HCM Center is the region’s only specialized HCM clinic, serving over 500 patients with this inherited condition. It brings together cardiologists with heart failure expertise, advanced imaging providers, electrophysiologists who are experts in the heart’s rhythm and electricity, and genetic counselors who provide guidance in personalized treatments and screening and prevention advice for family. And the center’s cardiac surgeons perform the highest number of septal myectomies in the region.

By adopting a team-based approach, the center delivers comprehensive care. That includes access to leading-edge clinical trials, genetic therapies, and genetic counseling.

“We are the only center in the state that provides access to multiple medical trials, many of which include gene therapy,” he says. “And we are closely collaborating with Children’s Hospital as we continue these research efforts.”

Additionally, Dr. Smith says the HCM Center is expanding access to new medications that will reduce the need for HCM surgery. Ultimately, he says, the center is dedicated to delivering the most advanced HCM services to patients just like Kenny.

“Having the center here has definitely improved care and outcomes for our patients,” he says. “The level of care they receive has expanded by 1,000-fold. It’s just amazing.”

The multidisciplinary care also includes a full range of services including diet and nutrition, rehabilitation and exercise, mental health support, and sleep medicine to ensure patients receive all the expert care they need to ensure the best outcomes.

Learn more about hypertrophic cardiomyopathy care at The Christ Hospital or call 513-648-5555.